Topic Categories

About Dávila

The Authentic Reactionary

The Epigraphs

This post is about a translation project regarding the aphorisms of Nicolás Gómez Dávila. He was a Colombian political philosopher in the Latin church, and his aphorisms do not necessarily reflect my own beliefs or opinions. They have been difficult to find in English, and are presented here in as complete a collection as possible for the purposes of enjoyment, study, and historical record. UPDATE: At last! Arcane Europa has recently published a selection of his aphorisms in English, with translations and commentary by Ramon Elani. I have not yet read it but I know Elani has long been interested in Dávila’s work and is well qualified for the task at hand, and I expect it is quite good!

List of Topics

(new categories typically posted Monday mornings)

Industrial Society

Intelligence (updated 12/5/23)

Journalism & Mass Media

Judgment

Justice & Mercy (updated 10/23)

Law & Custom

Letters

Literary Schools & Styles

Love

Man and Nature

The Mediocre & the Pedestrian

The Modern Man

Modernity

Morals, Ethics, & Values

Mystery & the Discreet

Nations & Cultures

Obscenity & Vulgarity

The People

The Philosopher

Philosophy

Political Parties & Movements

Politicians & Governance

Popular Opinion

Pride

Problems & Solutions

The Professional & the Intellectual

Progress

The Reactionary

Reading

Religion

Resignation

Revolution & Reform

The Revolutionary

Science

Sensibility

Sensuality & Sexuality

Social Justice & Utopia

Social Science & Psychology

Spirit

The State (updated 12/4/23)

Technology (updated 12/4/23)

Tradition

Truth

Understanding

Vanity

Virtue & Vice

Wealth & Want

The Writer

Writing (updated 11/30/23)

(to come: updates expanding on each category already posted! Plus: Aesthetics; Age & Death; The Aristocratic Soul; The Artist; The Arts; Atheism & Secularism; Authenticity; Capital; Civilization & Institutions; Communism & Socialism; Contemplation; Conviction; Criticism; The Crowd; Debasement; Decline & Collapse; Democracy; Discipline, Restraint, Austerity; Duty, Dignity, Nobility; Education & Academia; Enemies & Enmity; Envy; Equality & the Egalitarian; Evil, Sin, & Repentance; Faith; Foolishness; Freedom & Liberty; Gnosticism & Humanism; Happiness & Pleasures; Hierarchy; The Historian; History; Humility; Ideology)

The Aphorist

“I have never hoped for outsiders to favor me, unlike those who lament the place or time in which they were born;

I have had no ambition beyond that of achieving greatness in solitude.”

He wrote in fragments, and collected these aphorisms, or escolios (glosses) in notebooks. A voracious reader with a massive personal library and no university education, he studied primarily history, religion, and philosophy, and has a remark on nearly every topic. Read the collected aphorisms of Nicolás Gómez Dávila once, and you might find yourself wishing for a more clear philosophical or political system to follow. Read them again, and hopefully you’ll hear the man cautioning against such desires. Read them a third time and perhaps you’ll understand why.

“When we invent an all-encompassing meaning for the entire world,

we deprive of meaning even those fragments that do have meaning.”

Dávila offers no grand revolutionary plan for the future. He never points toward any possible utopia in this world, and warned against those who did. And while he knew there was no use trying to turn back to some previous imagined golden age, he did warn against modernity, progress, and even democracy, in spite of the taboos surrounding these topics. Rather than proposing yet another ultimately futile violent revolutionary plot in the name of undoing modernity, he took on a more frustrating task: being content to dispute the very notion that modernity and progress are natural and inevitable.

Dávila offers no grand revolutionary plan for the future. He never points toward any possible utopia in this world, and warned against those who did. And while he knew there was no use trying to turn back to some previous imagined golden age, he did warn against modernity, progress, and even democracy, in spite of the taboos surrounding these topics. Rather than proposing yet another ultimately futile violent revolutionary plot in the name of undoing modernity, he took on a more frustrating task: being content to dispute the very notion that modernity and progress are natural and inevitable.

“Nothing is more dangerous than man’s attitude today before his own works.

Until yesterday, man regarded every new invention with suspicion, fearing the presence of some diabolical power, and demanding that a long purgatory purify these disturbing creations.

Today, an excessive optimism, an unleashed faith in the benevolence of destiny and the goodness of human nature, induce him to joyfully embrace the fruit of human ingenuity.

It is impossible for modern man to believe that a new idea or invention can be pernicious or perverse; it is impossible for him to renounce its use because he imagines that in doing so he would disrespect a sacred obligation.”

“Progress, in the end, comes down to robbing man of what ennobles him,

in order to sell him at a cheap price that which degrades him.”

The fragments that Dávila gathered regarding religion, beauty, progress, tradition, the arts, and so on, make up the outlook of what he termed the Authentic Reactionary. (He wrote of this in one of his rare essay pieces, which you can read here.)

As for the use of the term, Jens Jessen writes in Die Zeit:

(The) contemporary public…can barely imagine anything other than a fascist, or in the best case scenario, a monarchist. Dávila, however, is neither. The reactionary is for him not at all a political activist who wants to restore old conditions, but rather a “passenger who suffers shipwreck with dignity.” The reactionary is “that fool, who possesses the vanity to judge history, and the immorality to come to terms with it.”…It is not easy to define his intellectual profile. In the ideological cartography of the West, his type can no longer be found. Not by accident did Gómez Dávila, who up until his death in 1994 hardly ever left his hometown of Bogotá, carry out his critique of modernity from the edge of the western world. He saw himself as an “authentic reactionary.”

The reader who recoils at the mere term may find Dávila more difficult to pin down, given an honest reading. Nobody makes it out alive: communism and capitalism are similarly excoriated, politicians of any and all ambition- indeed, ambition itself- are all dragged, the greed of the rich and the mediocrity of the bourgeois are gross but so is any romanticized notion of “the People.” He is not a mere propagandist, and saw firsthand the firing squads and devastation wrought by the zealot and the revolutionary during the period known as La Violencia—The Violence- when Colombian neighbors would literally kill one another over party affiliation. And so Dávila does not bother much with left vs right, nor does he use such terms interchangeably with liberal/conservative or democrat/republican- none of whom escape his criticism. The state, especially the bureaucratic, technocratic, impersonal State, is no friend of man, regardless of the party it represents. He does, however, focus on the progressive vs reactionary disposition: not merely in politics, but culturally, intellectually, in most all realms of life. While those may sound like just another version of the aforementioned political opposites, a closer look at the philosophical and moral underpinnings reveals something more, as Matthew Pheneger writes in Nicolás Gómez Dávila and the ‘Authentic Reactionary’:

There are…several recurring themes threaded throughout his work. Of particular significance are two principal archetypes…The first of these, which we might call the “Progressive Utopian,” is a champion of the dynamic forces of progress. Convinced that “the best always triumphs, because what triumphs is called the best,” the Progressive Utopian adheres to a teleological view of history. That is to say, he believes that history develops along rational lines until finally culminating in an inevitable end-point, like a river that winds and flows along its course until swallowed up by an implacable sea…The Progressive Utopian’s teleological worldview also goes some way in explaining his inherent attraction to messianic ideologies. Whether we speak of the Marxist “World Revolution” or the Neoliberal “End of History,” the Progressive Utopian persists in an enthusiastic belief in mankind’s capacity to both perfect itself and overcome the forces of nature. In doing so, he attempts anew the Promethean aspiration of myth.

Opposite the Progressive Utopian is the Authentic Reactionary. Uprooted and displaced by what the German writer Ernst Jünger characterized as the “great process, the Authentic Reactionary is that “fool who takes up the vanity of condemning history and the immorality of resigning himself to it.” Rather than fall in line with the programmatic goals delineated by the Progressive Utopian and his demolition squads, the Authentic Reactionary champions “causes that do not turn up on the notice board of history” and thereby attempts to piece together the fragments of a shattered world.

Dávila recognizes that sanity is not statistical, and that even a lost cause can still be the good one.

“To be reactionary is not to espouse settled cases, nor to plead for determined conclusions, but rather to submit our will to the necessity that does not constrain, to surrender our freedom to the exigency that does not compel; it is to find sleeping certainties that guide us to the edge of ancient pools. The reactionary is not a nostalgic dreamer of a canceled past, but rather a hunter of sacred shades upon the eternal hills.”

“To be reactionary is not to espouse settled cases, nor to plead for determined conclusions, but rather to submit our will to the necessity that does not constrain, to surrender our freedom to the exigency that does not compel; it is to find sleeping certainties that guide us to the edge of ancient pools. The reactionary is not a nostalgic dreamer of a canceled past, but rather a hunter of sacred shades upon the eternal hills.”

His rejection of both the liberal and conservative can be cutting, but the ultimate underpinning of his rejection springs from love and horror, not insecurity or a desire for power. Dávila describes a very specific type of reactionary, seeing himself as existing totally out of his time. Many of his positions are uncompromising and extreme, but his form of reaction is not one of belligerence and the aphorisms aren’t meant as an arsenal. Rather, he sees the reactionary as… “the guardian of every heritage- even the heritage of the revolutionary.” He believed we are witnessing the corrosion of the world by postmodern moral relativism and a general lack of common sense or values, and that resignation should never mean a cynical giving up and giving in, but rather taking refuge in the dignity and cultivation of the soul afforded by tradition and faith. The “glosses” are passionate yet sober, deadly serious yet full of humor, brilliant and self-deprecating, self-referential yet without any air-tight conclusive dogma. “My only pretension is that the book I have written is not linear, but concentric,” he writes, and it is true: they are best read slowly, in any order, and then again.

“When faced with the assaults of caprice,

authenticity needs a firm hold on principles in order to save itself.

Principles are bridges over the flash floods of life.”

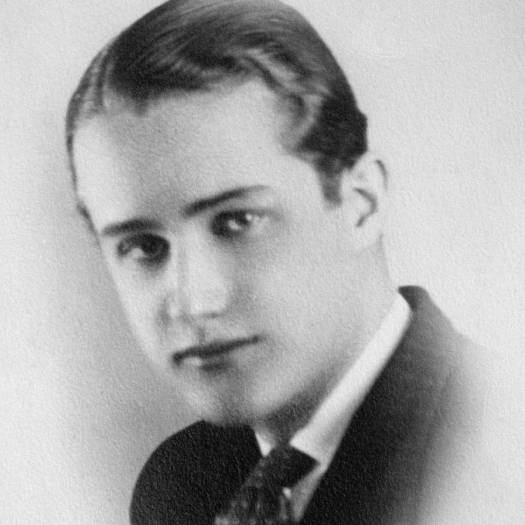

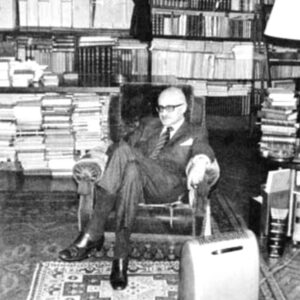

Born into a wealthy family in 1913 in Cajicá, Colombia (near Bogota), as a child, Dávila spent most of the year in a Benedictine-run school in Paris. While bed-bound with severe pneumonia for two years, he became fluent in Latin and Greek with the help of private tutors and came to love the classics. At 23 he returned to Bogota and wed Emilia Nieto Ramos. He rarely left Botoga after his return, and lived and died in that house. Their marriage would last until his death sixty years later. For a short time Dávila helped manage the family business, but soon passed it on to his son. He had learned French, English, Latin, and Greek in childhood, and eventually taught himself to read German, Italian, and Portuguese. His impressive library held 16,935 titles (totaling 27,582 volumes) in multiple languages and included some extremely rare works. It is now in the care of the Bank of the Republic of Colombia and is inventoried here.

There was no television set in the Dávila household, nor any daily newspaper. Visitors would enjoy an afternoon lunch followed by hours-long discussions in the library. Known as “don Colacho” to his friends, Dávila was a well-connected member of the Bogota elite and helped found the University of the Andes in 1948. A member of the Jockey Club, he had to give up polo after an injury, being thrown from a horse while trying to light a cigar. Politicians sought his advice, but he was determined to stay out of that sphere in any official capacity and turned down multiple offers of positions in politics and academia.

“To write honestly for others, you must write primarily for yourself.”

Dávila easily could have published to a wider degree in his lifetime, but rejected publishing offers until late in life and only then published with much reluctance. He did nothing whatsoever to attract attention to his work, apart from “self-publishing” a few dozen volumes for friends and family. Although Dávila’s work has now been translated into multiple languages around the globe, English translations tend to be severely abridged and difficult to find. It is possible that this is due to his unapologetic disdain for democracy and democratic institutions- the notion of democracy being a nearly untouchable taboo, especially in the US. As far as I know, as of this writing, I am preparing the largest collection of his works available in the English language.

“Democracy builds totalitarianism with liberal tools.”

Please note: His works were never arranged in the order that I offer them here. In the past, categorization by topic has attracted new readers to his work who may not otherwise be interested in wandering through over 3,500 aphorisms from some obscure Colombian author. But on the other hand, that audience misses out on the wandering. While the aphorisms are short and clever, lending themselves to individual use, they are properly part of an entire mindset and inform one another. To read and re-read is to experience the strange sensation of these glosses all becoming more enriched in ways you would not have expected, as you come to know the author and his sense of the world.

In order to encourage such exploration, each subject page will include a link to another. Do wander. Categories will post Mondays until they are complete. All will be under the Don Colacho category, which you can find in the drop-down menu.

Now that you’ve read my introduction, here is his own:

The Epigraphs

At the start of Escolios a un Texto Implícito, Dávila provides the following seven quotations as a guide, with no explanation or translation. Here, they are in English and with a bit of information!

1.

First, from Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. The old woman in question, who wins a medal at an agricultural show, is a farm worker. The chemist, an atheist.

Then, when she had her medal, she looked at it, and a smile of beatitude spread over her face; and as she walked away they could hear her muttering “I’ll give it to our cure up home, to say some masses for me!”

“What fanaticism!” exclaimed the chemist, leaning across to the notary.

“Stephen” of Don Colacho’s Aphorisms writes: “Gómez Dávila shows his courage and his sense of humor here. He knows how his writings will come across to most people, but he is not afraid of being called a fanatical Catholic. Not only that, but he even laughs at being called a fanatic, by associating himself with the old lady. Perhaps this excerpt from Madame Bovary was the inspiration for this aphorism: My convictions are the same as those of an old woman praying in the corner of a church.”

2.

The second is from Don Quixote by Cervantes. Here, Don Quixote discusses the rescue of Basilio with his squire Sancho, and Sancho only answers him in proverbs. Quixote responds like so:

“When are you going to stop, Sancho, a plague on you?” said Don Quixote. “When you begin to string together your proverbs and tales, only Judas himself would understand you—may he seize you. Tell me, blockhead, what do you know about spokes, or wheels, or anything else?”

“Well, if you don’t understand me,” rejoined Sancho, “it’s no wonder that my opinions are taken for nonsense. But no matter; I understand myself, and I know that I haven’t said many foolish things in my comments, only your worship is always an incensory of my sayings and even of my doings.”

“Censor, you should say,” replied Don Quixote, “and not incensory; confound you for a perverter of good language.”

Again, readers of Dávila will recognize that he is identifying with Sancho, not Quixote, and humorously, humbly informing the reader of the personal nature of the work.

3.

Diogenes Laërtius, third century Greek writer, provides the third quote:

few-lined, yet full of power.

4.

The fourth is from Shakespeare’s narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece.

For much imaginary work was there;

Conceit deceitful, so compact, so kind,

That for Achilles’ image stood his spear

Griped in an armed hand; himself, behind

Was left unseen, save to the eye of mind:

A hand, a foot, a leg, a head,

Stood for the whole to be imagined.

This surely refers to Dávila’s writing in aphorism.

5.

Paul Valéry’s Le Sylphe, a “puzzle poem,” which concerns inspiration and it’s source, provides the fifth epigraph.

Not seen, nor known,

I’m perfume spread

Living and dead

By the wind blown!Not seen, nor known,

Hazard or feat:

Hardly yet shown

The task’s complete!Unread, undelved?

In best minds shelved

What errors certs!Not known, not seen,

Time bare breasts lean

Between two shirts!

A mysterious poem such as this one is a fitting introduction to Dávila’s work, given his humility in the face of the insoluble problem, his rejection of cold rationalism and embrace of an authentic humanism, and a belief in sensuality as essential and good.

6.

The sixth bit is an excerpt from a letter from Friedrich Nietzsche to Danish intellectual Georg Brandes. (Here is the full letter in German.)

That what is involved here is the extended logic of a very definite philosophical sensibility and not a jumble of a hundred random paradoxes and heterodoxies—none of that has dawned, I believe, on even my most sympathetic readers.

Taken individually, a person could find anyone who agrees with at least one of Dávila’s individual aphorisms. The risk of my sharing them here grouped together by topic is that people will think that is all he had to say on the matter of politics, or religion, or art. In reality, they are all woven together as an entire system, a “very definite philosophical sensibility”- even the few which seemingly contradict one another at first glance. The more a person combs through them, the more aphorisms from totally disparate categories inform one another and the more rich they are all made.

7.

Finally, Francesco Petrarca, or Petrarch. In his letter to a friend, he explains his preference for the nighttime over the day, because the day only brings worries whereas the night brings silence. (The complete letter in Latin may be found here.) He asks for inner peace from the Lord, and ends the letter with something sounding not unlike an aphorism straight from Dávila himself.

And you wonder that I please few, and agree with few—I who perceive almost everything differently than does the crowd; I always consider the right path to be the one that is as far as possible from the crowd.

Sources:

Der Spiegel: Disenchanted World (archive)

Don Colacho’s Aphorisms: English translations of the aphorisms of Nicolás Gómez Dávila (archive)

Don Colacho’s Aphorisms: Epigraphs. This is the blog where I first came across Dávila’s work around 2015. The author has posted many of the same aphorisms, with the original Spanish. His translations are slightly different and less in number, and are not categorized in the same way.

The Imaginative Conservative: Nicolás Gómez Dávila and the ‘Authentic Reactionary’ (archive)

The Imaginative Conservative: Nicolás Gómez Dávila: The Nietzsche From the Andes (archive)

Intellectual Takeout: Nicolas Gomez-Davila’s Critique of Modernity (archive)

Martin Mosebach: A Hermit on the Edge of the Inhabited World (archive)

Philosophical Libraries: Private libraries of philosophers from the renaissance to the twentieth century (archive)

The Postil Magazine: Nicolás Gómez Dávila: An Authentic Reactionary’s Critique of Modernity (archive)

Die Zeit: The Last Reactionary (archive)

Featured image: Dávila in his youth.